19

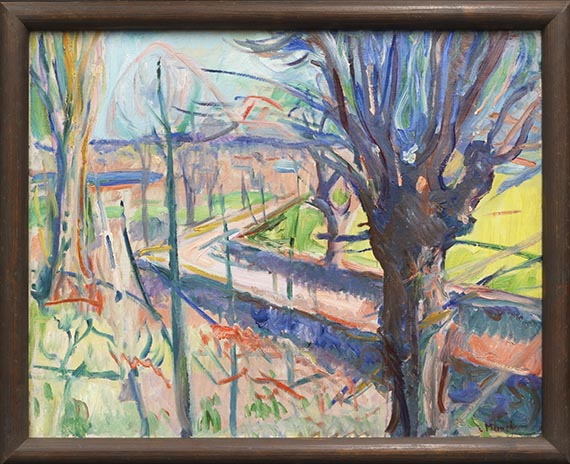

Edvard Munch

Frühlingstag auf Jeløya (Vårdag på Jeløya), 1915.

Oil on canvas

Estimation:

€ 700,000 / $ 812,000 Résultat:

€ 903,000 / $ 1,047,479 ( frais d'adjudication compris)

19

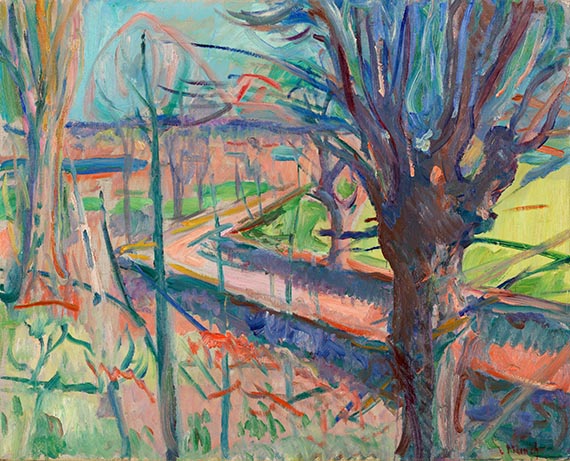

Edvard Munch

Frühlingstag auf Jeløya (Vårdag på Jeløya), 1915.

Oil on canvas

Estimation:

€ 700,000 / $ 812,000 Résultat:

€ 903,000 / $ 1,047,479 ( frais d'adjudication compris)

Edvard Munch

1863 - 1944

Frühlingstag auf Jeløya (Vårdag på Jeløya). 1915.

Oil on canvas.

Signed in the lower right. 65 x 80 cm (25.5 x 31.4 in).

• Alongside Vincent van Gogh and Henri Matisse, Edvard Munch is regarded as a pioneer of European Modernism due to his revolutionary ‘soul painting’.

• The emotional force of nature is Munch's central theme: ‘I felt that an infinite scream went through nature’ (Edvard Munch on the creation of ‘The Scream’).

• “Spring Day on Jeløya” (1915) – A mesmerizing landscape: Munch’s exhilarating celebration of life.

• Inspiration Expressionism: A rare example of Munch's intense stylistic exploration of the revolutionary works of the “Brücke” group.

• International exhibition history and an outstanding provenance: most recently part of the renowned Munch collection of Pal G. Gundersen.

PROVENANCE: Max Strasberg Collection (1884–1949), Wroclaw/Oslo (acquired directly from the artist in 1929).

Richard Mannheim (1883–1964) and Charlotte Mannheim, née Strasberg (1887–1976), London (brother-in-law and sister of the above).

Gallery Kaare Berntsen, Oslo.

Josephine Bay (1900–1962), New York (1961).

Robert M. Light, Boston.

Alfons Beaumont Landa Collection (1896–1991), Palm Beach (until 1977, Parke-Bernet, New York).

Private collection, Stockholm (probably acquired from the above in 1977).

Bertil and Greta Albinsson Collection, Ballingslöv and Hässleholm (until 2013).

The Gundersen Collection, Oslo.

EXHIBITION: Blomqvist Kunsthandel, Kristiania, 1915, cat. no. 26 (under the title “Vårbilde”).

Munch og malervennene, Blaafarveværket, Modum, 2013, cat. no. 83 (with illustration on p. 199).

Munch!, Thielska Galleriet, Stockholm, February 9–May 12, 2013, no cat.

Fruktbar Jord. Edvard Munch, Galleri F 15, Moss, June 18–September 21, 2016, pp. 38f. (with color illustration, no cat.).

Scream & Respond, Shanghai Jiushi Art Museum, September 25, 2020–January 3, 2021, no cat.

Edvard Munch. Beyond the Scream, Hangaram Art Museum, Seoul, May 22–September 19, 2024, p. 161 and 273, no number.

LITERATURE: Gerd Woll, Edvard Munch Complete Paintings Catalogue Raisonné, volume III, Oslo 2009, CR no. 1139 (with illustration on p. 1078).

Edvard Munch - Catalogue Raissonné, digital catalog of works, No. PE.M.00198 (https://www.munch.no/en/object/PE.M.00198).

- -

Curt Glaser, Edvard Munch, Berlin 1922, p. 197 (illustration).

Curt Glaser, Edvard Munch, in: Der Cicerone: Halbmonatsschrift für die Interessen des Kunstforschers & Sammlers, 16.1924, no. 21, pp. 1110-1119, here ill. on p. 1117.

Sotheby's, London, March 31, 1965, lot 101 (with color illustration).

Sotheby's, London, April 26, 1967, lot 69 (with color illustration).

Parke-Bernet, New York, May 11, 1977, lot 51 (with color illustration).

Frank Høifødt, Fruktbar jord. Munch i Moss 1913-1916. Utgivelse i forbindelse med utstilling på Galleri F 15, Jeløya, Moss 2016, pp. 42f.

Guro Dyvesveen, Edvard Munch i Moss 1913-1916. Undervisningshefte for 7. trinn, Moss 2016, pp. 68f.

Hans-Martin Frydenberg Flaatten, Edvard Munch in Moss. Kunst, krig og kapital på Jeløy 1913-1916, Moss 2014, p. 243.

ARCHIVE MATERIAL:

Exhibition view at Blomqvist Kunsthandel, Kristiania 1915.

Max Strasberg to Edvard Munch, Archive of the Munch Museum Oslo, letters no. K 3367 (July 31, 1928), K 3368 (September 13, 1928), K 3370. (July 9, 1929), K 3371 (August 10, 1929).

“I 've dreamt about these works! And I realize that I reacted to them just as people reacted to my works years ago.”

Edvard Munch to Gustav Schiefler about Karl Schmidt-Rottluff's prints.

“I have always tried to express my feelings and thoughts through my art."

Edvard Munch

"Munch poses a question that he would pursue until his death in 1944: To what extent can artists convey their innermost thoughts and feelings using lines, forms, and colors?"

Annemarie Iker, 2020, Museum of Modern Art, New York.

"I have always been drawn to artists with a powerful and direct work. You feel this in the art of Pablo Picasso, of Egon Schiele, of Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. And you definitely feel this in the art of Edvard Munch."

Ronald S. Lauder, President, Neue Galerie, New York

1863 - 1944

Frühlingstag auf Jeløya (Vårdag på Jeløya). 1915.

Oil on canvas.

Signed in the lower right. 65 x 80 cm (25.5 x 31.4 in).

• Alongside Vincent van Gogh and Henri Matisse, Edvard Munch is regarded as a pioneer of European Modernism due to his revolutionary ‘soul painting’.

• The emotional force of nature is Munch's central theme: ‘I felt that an infinite scream went through nature’ (Edvard Munch on the creation of ‘The Scream’).

• “Spring Day on Jeløya” (1915) – A mesmerizing landscape: Munch’s exhilarating celebration of life.

• Inspiration Expressionism: A rare example of Munch's intense stylistic exploration of the revolutionary works of the “Brücke” group.

• International exhibition history and an outstanding provenance: most recently part of the renowned Munch collection of Pal G. Gundersen.

PROVENANCE: Max Strasberg Collection (1884–1949), Wroclaw/Oslo (acquired directly from the artist in 1929).

Richard Mannheim (1883–1964) and Charlotte Mannheim, née Strasberg (1887–1976), London (brother-in-law and sister of the above).

Gallery Kaare Berntsen, Oslo.

Josephine Bay (1900–1962), New York (1961).

Robert M. Light, Boston.

Alfons Beaumont Landa Collection (1896–1991), Palm Beach (until 1977, Parke-Bernet, New York).

Private collection, Stockholm (probably acquired from the above in 1977).

Bertil and Greta Albinsson Collection, Ballingslöv and Hässleholm (until 2013).

The Gundersen Collection, Oslo.

EXHIBITION: Blomqvist Kunsthandel, Kristiania, 1915, cat. no. 26 (under the title “Vårbilde”).

Munch og malervennene, Blaafarveværket, Modum, 2013, cat. no. 83 (with illustration on p. 199).

Munch!, Thielska Galleriet, Stockholm, February 9–May 12, 2013, no cat.

Fruktbar Jord. Edvard Munch, Galleri F 15, Moss, June 18–September 21, 2016, pp. 38f. (with color illustration, no cat.).

Scream & Respond, Shanghai Jiushi Art Museum, September 25, 2020–January 3, 2021, no cat.

Edvard Munch. Beyond the Scream, Hangaram Art Museum, Seoul, May 22–September 19, 2024, p. 161 and 273, no number.

LITERATURE: Gerd Woll, Edvard Munch Complete Paintings Catalogue Raisonné, volume III, Oslo 2009, CR no. 1139 (with illustration on p. 1078).

Edvard Munch - Catalogue Raissonné, digital catalog of works, No. PE.M.00198 (https://www.munch.no/en/object/PE.M.00198).

- -

Curt Glaser, Edvard Munch, Berlin 1922, p. 197 (illustration).

Curt Glaser, Edvard Munch, in: Der Cicerone: Halbmonatsschrift für die Interessen des Kunstforschers & Sammlers, 16.1924, no. 21, pp. 1110-1119, here ill. on p. 1117.

Sotheby's, London, March 31, 1965, lot 101 (with color illustration).

Sotheby's, London, April 26, 1967, lot 69 (with color illustration).

Parke-Bernet, New York, May 11, 1977, lot 51 (with color illustration).

Frank Høifødt, Fruktbar jord. Munch i Moss 1913-1916. Utgivelse i forbindelse med utstilling på Galleri F 15, Jeløya, Moss 2016, pp. 42f.

Guro Dyvesveen, Edvard Munch i Moss 1913-1916. Undervisningshefte for 7. trinn, Moss 2016, pp. 68f.

Hans-Martin Frydenberg Flaatten, Edvard Munch in Moss. Kunst, krig og kapital på Jeløy 1913-1916, Moss 2014, p. 243.

ARCHIVE MATERIAL:

Exhibition view at Blomqvist Kunsthandel, Kristiania 1915.

Max Strasberg to Edvard Munch, Archive of the Munch Museum Oslo, letters no. K 3367 (July 31, 1928), K 3368 (September 13, 1928), K 3370. (July 9, 1929), K 3371 (August 10, 1929).

“I 've dreamt about these works! And I realize that I reacted to them just as people reacted to my works years ago.”

Edvard Munch to Gustav Schiefler about Karl Schmidt-Rottluff's prints.

“I have always tried to express my feelings and thoughts through my art."

Edvard Munch

"Munch poses a question that he would pursue until his death in 1944: To what extent can artists convey their innermost thoughts and feelings using lines, forms, and colors?"

Annemarie Iker, 2020, Museum of Modern Art, New York.

"I have always been drawn to artists with a powerful and direct work. You feel this in the art of Pablo Picasso, of Egon Schiele, of Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. And you definitely feel this in the art of Edvard Munch."

Ronald S. Lauder, President, Neue Galerie, New York

Edvard Munch – Pioneer of European Modernism and a driving force for an entire century

Edvard Munch ranks alongside Vincent van Gogh and Henri Matisse as one of the pioneers of European Modernism. Without them and their audacious drive for innovation, Expressionism, especially the art of the “Brücke” and the “Blauer Reiter,” would not have been possible. They were the driving forces at the end of the 19th century, when the future European art capitals of Berlin and Paris were still dominated by classical salon art and history painting, yet they were trying out radically new approaches. The paintings of the young Norwegian Edvard Munch hit Berlin like a meteorite in 1892. After only a few days, his exhibition, organized at the invitation of the ‘Verein Berliner Künstler’ (Berlin Artists' Association) at the instigation of Anton von Werner, director of the Royal Academy of Fine Arts, was closed amid protests and clashes among the association's members. But the scandal surrounding Munch's new style of painting, which was perceived as crude and unfinished, had shaken up the conservative Berlin art scene once and for all and made the young painter famous in Germany overnight. Munch sparked a kind of big bang in Berlin, enabling the founding of the Berlin Secession under the directorship of Max Liebermann a few years later and the emergence of Expressionism shortly thereafter. Munch's nonconformity, his incredibly emotional painting style that broke with all academic traditions, was to become one of the most important forces for the European avant-garde. His courageous painting was, in many ways, a constant source of inspiration for the young generation of artists of the Berlin “Brücke” Expressionists, for Emil Nolde, Max Pechstein, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, and—in terms of the expression of psychological extremes—also for Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. Thanks to its maximally liberated style, highly emotional expression, and iconic motifs, Munch's epochal painting also provided decisive impulses for many artists active in the second half of the century and even for contemporary art. Numerous names that reach far beyond the 20th century could be mentioned here, but above all, Andy Warhol, Peter Doig, Georg Baselitz, Marlene Dumas, Jasper Jones, and Tracey Emin deserve special mention.

Life, love, fear, and death—Munch as a master of the Nordic soulscape

It is the highly emotional perception of nature that Munch himself, after his Impressionist beginnings, describes as a personal artistic awakening; an experience that inspired his four versions of “The Scream,” paintings that are considered iconic today: “I was walking down the street with two friends – as the sun was setting – when the sky suddenly turned blood red [...] above the blue-black fjord and the city lay blood and tongues of fire – [...] and I stood there trembling with fear – and I felt that an infinite scream went through nature.” Through the distorted yet symbiotic connection between nature and man, Munch was the first to capture the existential feeling of fear on canvas. Having had a childhood marked by painful experiences due to the early death of his mother and his beloved sister Sophie, and later having to process several unhappy romantic relationships through his art, Munch became the painter of existential emotional worlds between life, love, fear, and death. These are the abstract yet universally human themes that Munch also summarized in the paintings of his famous “Life Frieze”. The “Life Frieze” was first presented to the public in a separate exhibition room at the fifth exhibition of the Berlin Secession in 1902. One of the most famous paintings in this group of works is “The Dance of Life” (1899/1900, Norwegian National Gallery, Oslo), of which Munch painted a second version in 1925 (Munch Museet, Oslo). In a Norwegian fjord landscape, Munch depicts dancing figures symbolizing life, love, and death against the backdrop of a melancholic sunset into the sea. But Munch, who was severely mentally and physically ill throughout his life, also repeatedly painted deserted landscapes that, due to the melancholic and nervous disposition of the highly sensitive painter, always appear to us as intimate and captivating ‘soulscapes’ of the artist.

“Spring Day on Jeløya” is not only an outstanding example of this spontaneous and almost intoxicating ‘soul painting’, but also of Munch's undisputed mastery of color and composition, with which he captured the vastness and bright light of the Nordic landscape in the form of a loose and freely set arrangement of lines. With virtuosity and courage, Munch spread a colorful structure of brushstrokes across the canvas. Seen up close, it appears almost abstract, but from a distance, it merges in the viewer's eye in a nearly miraculous way to form a radiant Nordic landscape that conveys an intense feeling of vastness, light, and exuberant vitality.

“Spring Day on Jeløya” (1915) – Munch's exhilarating affirmation of life

Ronald S. Lauder, one of the world's most renowned collectors of modern art and president of the Neue Galerie in New York, aptly described the special emotional power that Munch's magnificent creations exude, and which his oeuvre shares with that of other outstanding artists such as Pablo Picasso, Egon Schiele, and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, in the following words:"I have always been drawn to artists whose work is powerful and direct. You feel this in the art of Pablo Picasso, of Egon Schiele, of Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. And you definitely feel this in the art of Edvard Munch. […] His images relate to primal emotions shared by all human beings: loneliness, anxiety, jealousy. But they are rendered in such a way that we also feel the beauty of existence, the pleasures of color and form. Simply put, Munch is a master."(Ronald S. Lauder, President of the Neue Galerie, New York, quoted from: Foreword, exhibition catalog Munch and Expressionism, New York 2016, p. 7)

In “Spring Day on Jeløya,” it is not a sensation of fear or despair, but rather a spirit of vitality and joy that captivates the viewer through the vibrant, vernal colors and the vigorously expansive shapes of the plants and trees. Munch's painting pays homage to the eternal forces of life between becoming and perishing, life and death: “Spring Day on Jeløya,” however, is dedicated to life.

In 1913, while Ernst Ludwig Kirchner was painting his famous street scenes in Berlin to capture the hectic pace of city life on canvas, Edvard Munch, who had returned to Norway from Berlin in 1909, rented the Grimsrød estate on the island of Jeløya as his artistic retreat. As the older and much better-known artist, Munch had been somewhat reserved in his response to the numerous advances of the “Brücke” artists during his last years in Germany, and ultimately, participating in the “Brücke” exhibition in 1908, to which Karl Schmidt-Rottluff had invited him, was no longer possible, also for health reasons. Due to years of alcohol and drug abuse, Munch suffered a mental and physical breakdown, experienced severe hallucinations and paranoia, and was eventually admitted to Professor Daniel Jacobson's psychiatric clinic in Copenhagen. This stay in the clinic, which was by no means Munch's first, lasted seven months, and the artist was ultimately diagnosed with manic-depressive disorder. Like Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Munch was highly sensitive and suffered from an anxiety disorder caused by an early childhood trauma, which drove him into years of alcohol and drug addiction. Just as Kirchner ultimately sought strength, stability, and peace in the Swiss mountains from 1918 onward, Munch also found a temporary refuge from the often overwhelming demands of the world and being an artist on the Norwegian island of Jeløya in the Oslo Fjord from 1913 onward. In the previous years, Munch had participated in numerous exhibitions throughout Europe, among them the significant Sonderbund Exhibition in Cologne in 1912. He had traveled extensively and had hardly had a moment's rest. This was to change in the solitude of Jeløya Island, for after his discharge from the sanatorium, Munch had gradually renounced all social relationships and obligations and henceforth remained in contact with only a few old friends.

Although Munch continued to explore his central theme of the early and traumatic death of his beloved sister Sophie during his time on Jeløya in paintings such as “On Her Deathbed” (1915, Art Museum, Rasmus Meyer Collection, Bergen), the landscape paintings he produced during his short stay on the island are characterized by a hopeful mood, even if, in some cases—especially in the snow and fjord landscapes in winter-Munch's focus is once again on the melancholic heaviness of our mortality. “Spring Day on Jeløya" is one of Munch's rare paintings that represents a clear commitment to the beauty of life, that pays artistic homage to the forces of spring, that celebrates the beauty and transience of the moment, and thus, at least indirectly, how could it be otherwise for Munch, bears an awareness of the finiteness of everything beautiful.

It is the reflection on one's own mortality, so central to Munch's seminal work, that resonates here, the awareness of the vulnerability and transience of our own existence in the face of the eternal spectacle of nature. This thought is also inherent in the romantic paintings of Caspar David Friedrich, for example, when he confronts his “Monk by the Sea” (1808/10) or his “Wanderer above the Sea of Fog” (1818) with an overwhelming spectacle of nature. Unlike Friedrich, however, Munch uses the depiction of nature not only as a symbol of the eternally sublime but rather as a reflection of his own state of mind, as an almost intoxicating attempt to give artistic expression to his feelings.

“Spring Day on Jeløya” is a special painting, not least because it provides clear stylistic evidence of the intense exchange between Munch, the pioneer of Modernism, and the young “Brücke” Expressionists, who were inspired by his visionary painting. This exchange was mutually enriching, as can be seen, because Munch was also captivated by the powerful, clearly defined formal language of the young Germans. In “Spring Day on Jeløya,” the sharply edged path running in a V-shape toward the sea seems like a reference to the clear, angular forms of the Expressionists, which Munch skillfully blends with the Nordic ‘soulscape’ he brought to perfection. According to Gustav Schiefler's diary entry, Munch is said to have remarked, after seeing prints by Karl Schmidt-Rottluff at the home of the Hamburg collector and author of a catalogue raisonné: “I have dreamed of these works! And I realized that I reacted to them in the same way that people reacted to my works years ago.” [JS]

On the provenance

The story behind Edvard Munch's “Spring Day on Jeløya” is one of fascinating personalities. The adjective “fascinating” undoubtedly applies to the artist himself. The painter became a legend at an early stage. And even though Munch regularly exhibited his works in renowned exhibitions—our painting, for example, was shown at an exhibition organized by his gallerist, Blomqvist, in 1915 (fig.)—he did not make it easy for collectors to acquire his paintings. Curt Glaser, one of the painter's greatest admirers, reports on this mindset in his essay “Besuch bei Munch” (Visiting Munch), which is well worth reading. The painter had two buildings erected in his garden to store his works rather than sell them. “You see,” Munch explained to him, "there are painters who collect other people's paintings [...]. I need my own paintings just as much. I need to have them around me if I want to continue working." (Kunst und Künstler, 25.1927, issue 6, esp. p. 205f., here p. 205.)

And so Munch feared nothing more than the possibility that one of his paintings might actually be purchased. He attempted to prevent the inevitable by charging exorbitant prices.

"Application" of a collector

It took around five years before Munch was finally willing to part with “Spring Day on Jeløya.” Letters to the artist by Max Strasberg, a traveling salesman from Wroclaw and owner of an art supply store, attest to this. Today, these letters are preserved at the Munch Museum in Oslo. His father, Israel, was already known as an art collector (“Maecenas,” 1930). It is therefore no surprise that Max Strasberg, who apparently traveled frequently to the north on business and was fluent in Norwegian, also tried his luck: he wanted to purchase a painting by the great Edvard Munch.

As early as 1924, Strasberg asked Munch if he could buy a small painting from him. He had been trying to do so for a long time, but the paintings were too expensive in Germany (letter K 3366). Then, in the summer of 1928, came the next attempt: "I take the liberty of writing to you & politely asking whether you would perhaps be willing to paint an oil painting for me for 2000 kroner. – Some time ago, I saw one at Blomqvist [...] that I liked very much, and I would like to own such a landscape [...] and take it with me to my home in Wroclaw. I hereby give you my word of honor that I am not looking to speculate, but that I am a modest collector and already own several of your lithographs and woodcuts. I kindly ask you to paint such a landscape for me [...]". (Letter K 3367)

Although the letters in which Munch replied to Strasberg have not been preserved, Strasberg's own correspondence provides sufficient information about the further course of this peculiar “application process”: they met in person. In September 1928, Strasberg expressed his gratitude for the meeting, during which Munch showed him his large collection of paintings in storage. There was clearly mutual sympathy, and so it was agreed that Strasberg would indeed receive a work. Which one exactly, however, was of course left to the artist to choose. And not immediately – Strasberg had to continue to plead: "I apologize once again that I can only pay you 2,500 kroner [...]; I am of course happy with a small painting, and I promise you once again that I will never mention the price to anyone else [...] P.S. Best regards to your two lovely dogs." (Letter K 3368)

... never give up

But even the charming greeting to Munch's pets did not help the Wroclaw collector at first. On December 18 of the same year, Strasberg still had no painting in sight (letter K 3369). In 1929, however, he finally succeeded. A postcard from Jeløya from July of that year bears the first trace of our work. Strasberg wrote to Munch in Norwegian: “Allow me to send you my best regards from Jeløen. As you will remember, I was very fortunate to acquire one of your paintings from there some time ago.” (Letter K 3370)

Max Strasberg wrote more specifically a few weeks later. He had the painting reframed in Wrocław, and it had already been shown to the director of the local art museum, who reacted enthusiastically. “I believe the museum here in Wrocław would like to borrow the painting from me for four to six weeks, and I don’t want to refuse the request, because it will give many less affluent people the opportunity to see something beautiful.” (Letter KK 3371)

So Strasberg had succeeded. After five years of persistent requests, he had finally become the owner of a Munch painting: “Spring Day on Jeløya.”

The further fate of Max Strasberg remains hidden in the darkness of history. As a Jew, he was persecuted by the Nazi regime, and apparently tried to leave as few traces as possible during these difficult years. He died in his adopted home of Oslo in 1949 without any direct descendants. “Spring Day on Jeløya” went to his sister, Charlotte, and her husband, Richard Mannheim, who were living in exile in London.

The "Who is Who" of the "Spring Day"

The other famous owners of “Spring Day on Jeløya” read like a “Who's Who” of the 20th century: they include the legendary US financial expert and entrepreneur Josephine Bay (1900–1961) (her husband Charles Ulrich Bay was ambassador to Oslo from 1946 to 1953). Alfons Beaumont Landa, a lawyer and businessman from Palm Beach, was also a social figure of his time – the New York Times even reported on his six-year-old son's birthday party in 1967. Last but not least, of course, is Pål G. Gundersen, who built up an impressive collection of Norwegian art over many decades and is considered a keen expert on Munch. Now “Spring Day on Jeløya” from this remarkable collection is up for auction, allowing a new collector to continue the line of distinguished owners. [AT]

Edvard Munch ranks alongside Vincent van Gogh and Henri Matisse as one of the pioneers of European Modernism. Without them and their audacious drive for innovation, Expressionism, especially the art of the “Brücke” and the “Blauer Reiter,” would not have been possible. They were the driving forces at the end of the 19th century, when the future European art capitals of Berlin and Paris were still dominated by classical salon art and history painting, yet they were trying out radically new approaches. The paintings of the young Norwegian Edvard Munch hit Berlin like a meteorite in 1892. After only a few days, his exhibition, organized at the invitation of the ‘Verein Berliner Künstler’ (Berlin Artists' Association) at the instigation of Anton von Werner, director of the Royal Academy of Fine Arts, was closed amid protests and clashes among the association's members. But the scandal surrounding Munch's new style of painting, which was perceived as crude and unfinished, had shaken up the conservative Berlin art scene once and for all and made the young painter famous in Germany overnight. Munch sparked a kind of big bang in Berlin, enabling the founding of the Berlin Secession under the directorship of Max Liebermann a few years later and the emergence of Expressionism shortly thereafter. Munch's nonconformity, his incredibly emotional painting style that broke with all academic traditions, was to become one of the most important forces for the European avant-garde. His courageous painting was, in many ways, a constant source of inspiration for the young generation of artists of the Berlin “Brücke” Expressionists, for Emil Nolde, Max Pechstein, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, and—in terms of the expression of psychological extremes—also for Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. Thanks to its maximally liberated style, highly emotional expression, and iconic motifs, Munch's epochal painting also provided decisive impulses for many artists active in the second half of the century and even for contemporary art. Numerous names that reach far beyond the 20th century could be mentioned here, but above all, Andy Warhol, Peter Doig, Georg Baselitz, Marlene Dumas, Jasper Jones, and Tracey Emin deserve special mention.

Life, love, fear, and death—Munch as a master of the Nordic soulscape

It is the highly emotional perception of nature that Munch himself, after his Impressionist beginnings, describes as a personal artistic awakening; an experience that inspired his four versions of “The Scream,” paintings that are considered iconic today: “I was walking down the street with two friends – as the sun was setting – when the sky suddenly turned blood red [...] above the blue-black fjord and the city lay blood and tongues of fire – [...] and I stood there trembling with fear – and I felt that an infinite scream went through nature.” Through the distorted yet symbiotic connection between nature and man, Munch was the first to capture the existential feeling of fear on canvas. Having had a childhood marked by painful experiences due to the early death of his mother and his beloved sister Sophie, and later having to process several unhappy romantic relationships through his art, Munch became the painter of existential emotional worlds between life, love, fear, and death. These are the abstract yet universally human themes that Munch also summarized in the paintings of his famous “Life Frieze”. The “Life Frieze” was first presented to the public in a separate exhibition room at the fifth exhibition of the Berlin Secession in 1902. One of the most famous paintings in this group of works is “The Dance of Life” (1899/1900, Norwegian National Gallery, Oslo), of which Munch painted a second version in 1925 (Munch Museet, Oslo). In a Norwegian fjord landscape, Munch depicts dancing figures symbolizing life, love, and death against the backdrop of a melancholic sunset into the sea. But Munch, who was severely mentally and physically ill throughout his life, also repeatedly painted deserted landscapes that, due to the melancholic and nervous disposition of the highly sensitive painter, always appear to us as intimate and captivating ‘soulscapes’ of the artist.

“Spring Day on Jeløya” is not only an outstanding example of this spontaneous and almost intoxicating ‘soul painting’, but also of Munch's undisputed mastery of color and composition, with which he captured the vastness and bright light of the Nordic landscape in the form of a loose and freely set arrangement of lines. With virtuosity and courage, Munch spread a colorful structure of brushstrokes across the canvas. Seen up close, it appears almost abstract, but from a distance, it merges in the viewer's eye in a nearly miraculous way to form a radiant Nordic landscape that conveys an intense feeling of vastness, light, and exuberant vitality.

“Spring Day on Jeløya” (1915) – Munch's exhilarating affirmation of life

Ronald S. Lauder, one of the world's most renowned collectors of modern art and president of the Neue Galerie in New York, aptly described the special emotional power that Munch's magnificent creations exude, and which his oeuvre shares with that of other outstanding artists such as Pablo Picasso, Egon Schiele, and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, in the following words:"I have always been drawn to artists whose work is powerful and direct. You feel this in the art of Pablo Picasso, of Egon Schiele, of Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. And you definitely feel this in the art of Edvard Munch. […] His images relate to primal emotions shared by all human beings: loneliness, anxiety, jealousy. But they are rendered in such a way that we also feel the beauty of existence, the pleasures of color and form. Simply put, Munch is a master."(Ronald S. Lauder, President of the Neue Galerie, New York, quoted from: Foreword, exhibition catalog Munch and Expressionism, New York 2016, p. 7)

In “Spring Day on Jeløya,” it is not a sensation of fear or despair, but rather a spirit of vitality and joy that captivates the viewer through the vibrant, vernal colors and the vigorously expansive shapes of the plants and trees. Munch's painting pays homage to the eternal forces of life between becoming and perishing, life and death: “Spring Day on Jeløya,” however, is dedicated to life.

In 1913, while Ernst Ludwig Kirchner was painting his famous street scenes in Berlin to capture the hectic pace of city life on canvas, Edvard Munch, who had returned to Norway from Berlin in 1909, rented the Grimsrød estate on the island of Jeløya as his artistic retreat. As the older and much better-known artist, Munch had been somewhat reserved in his response to the numerous advances of the “Brücke” artists during his last years in Germany, and ultimately, participating in the “Brücke” exhibition in 1908, to which Karl Schmidt-Rottluff had invited him, was no longer possible, also for health reasons. Due to years of alcohol and drug abuse, Munch suffered a mental and physical breakdown, experienced severe hallucinations and paranoia, and was eventually admitted to Professor Daniel Jacobson's psychiatric clinic in Copenhagen. This stay in the clinic, which was by no means Munch's first, lasted seven months, and the artist was ultimately diagnosed with manic-depressive disorder. Like Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Munch was highly sensitive and suffered from an anxiety disorder caused by an early childhood trauma, which drove him into years of alcohol and drug addiction. Just as Kirchner ultimately sought strength, stability, and peace in the Swiss mountains from 1918 onward, Munch also found a temporary refuge from the often overwhelming demands of the world and being an artist on the Norwegian island of Jeløya in the Oslo Fjord from 1913 onward. In the previous years, Munch had participated in numerous exhibitions throughout Europe, among them the significant Sonderbund Exhibition in Cologne in 1912. He had traveled extensively and had hardly had a moment's rest. This was to change in the solitude of Jeløya Island, for after his discharge from the sanatorium, Munch had gradually renounced all social relationships and obligations and henceforth remained in contact with only a few old friends.

Although Munch continued to explore his central theme of the early and traumatic death of his beloved sister Sophie during his time on Jeløya in paintings such as “On Her Deathbed” (1915, Art Museum, Rasmus Meyer Collection, Bergen), the landscape paintings he produced during his short stay on the island are characterized by a hopeful mood, even if, in some cases—especially in the snow and fjord landscapes in winter-Munch's focus is once again on the melancholic heaviness of our mortality. “Spring Day on Jeløya" is one of Munch's rare paintings that represents a clear commitment to the beauty of life, that pays artistic homage to the forces of spring, that celebrates the beauty and transience of the moment, and thus, at least indirectly, how could it be otherwise for Munch, bears an awareness of the finiteness of everything beautiful.

It is the reflection on one's own mortality, so central to Munch's seminal work, that resonates here, the awareness of the vulnerability and transience of our own existence in the face of the eternal spectacle of nature. This thought is also inherent in the romantic paintings of Caspar David Friedrich, for example, when he confronts his “Monk by the Sea” (1808/10) or his “Wanderer above the Sea of Fog” (1818) with an overwhelming spectacle of nature. Unlike Friedrich, however, Munch uses the depiction of nature not only as a symbol of the eternally sublime but rather as a reflection of his own state of mind, as an almost intoxicating attempt to give artistic expression to his feelings.

“Spring Day on Jeløya” is a special painting, not least because it provides clear stylistic evidence of the intense exchange between Munch, the pioneer of Modernism, and the young “Brücke” Expressionists, who were inspired by his visionary painting. This exchange was mutually enriching, as can be seen, because Munch was also captivated by the powerful, clearly defined formal language of the young Germans. In “Spring Day on Jeløya,” the sharply edged path running in a V-shape toward the sea seems like a reference to the clear, angular forms of the Expressionists, which Munch skillfully blends with the Nordic ‘soulscape’ he brought to perfection. According to Gustav Schiefler's diary entry, Munch is said to have remarked, after seeing prints by Karl Schmidt-Rottluff at the home of the Hamburg collector and author of a catalogue raisonné: “I have dreamed of these works! And I realized that I reacted to them in the same way that people reacted to my works years ago.” [JS]

On the provenance

The story behind Edvard Munch's “Spring Day on Jeløya” is one of fascinating personalities. The adjective “fascinating” undoubtedly applies to the artist himself. The painter became a legend at an early stage. And even though Munch regularly exhibited his works in renowned exhibitions—our painting, for example, was shown at an exhibition organized by his gallerist, Blomqvist, in 1915 (fig.)—he did not make it easy for collectors to acquire his paintings. Curt Glaser, one of the painter's greatest admirers, reports on this mindset in his essay “Besuch bei Munch” (Visiting Munch), which is well worth reading. The painter had two buildings erected in his garden to store his works rather than sell them. “You see,” Munch explained to him, "there are painters who collect other people's paintings [...]. I need my own paintings just as much. I need to have them around me if I want to continue working." (Kunst und Künstler, 25.1927, issue 6, esp. p. 205f., here p. 205.)

And so Munch feared nothing more than the possibility that one of his paintings might actually be purchased. He attempted to prevent the inevitable by charging exorbitant prices.

"Application" of a collector

It took around five years before Munch was finally willing to part with “Spring Day on Jeløya.” Letters to the artist by Max Strasberg, a traveling salesman from Wroclaw and owner of an art supply store, attest to this. Today, these letters are preserved at the Munch Museum in Oslo. His father, Israel, was already known as an art collector (“Maecenas,” 1930). It is therefore no surprise that Max Strasberg, who apparently traveled frequently to the north on business and was fluent in Norwegian, also tried his luck: he wanted to purchase a painting by the great Edvard Munch.

As early as 1924, Strasberg asked Munch if he could buy a small painting from him. He had been trying to do so for a long time, but the paintings were too expensive in Germany (letter K 3366). Then, in the summer of 1928, came the next attempt: "I take the liberty of writing to you & politely asking whether you would perhaps be willing to paint an oil painting for me for 2000 kroner. – Some time ago, I saw one at Blomqvist [...] that I liked very much, and I would like to own such a landscape [...] and take it with me to my home in Wroclaw. I hereby give you my word of honor that I am not looking to speculate, but that I am a modest collector and already own several of your lithographs and woodcuts. I kindly ask you to paint such a landscape for me [...]". (Letter K 3367)

Although the letters in which Munch replied to Strasberg have not been preserved, Strasberg's own correspondence provides sufficient information about the further course of this peculiar “application process”: they met in person. In September 1928, Strasberg expressed his gratitude for the meeting, during which Munch showed him his large collection of paintings in storage. There was clearly mutual sympathy, and so it was agreed that Strasberg would indeed receive a work. Which one exactly, however, was of course left to the artist to choose. And not immediately – Strasberg had to continue to plead: "I apologize once again that I can only pay you 2,500 kroner [...]; I am of course happy with a small painting, and I promise you once again that I will never mention the price to anyone else [...] P.S. Best regards to your two lovely dogs." (Letter K 3368)

... never give up

But even the charming greeting to Munch's pets did not help the Wroclaw collector at first. On December 18 of the same year, Strasberg still had no painting in sight (letter K 3369). In 1929, however, he finally succeeded. A postcard from Jeløya from July of that year bears the first trace of our work. Strasberg wrote to Munch in Norwegian: “Allow me to send you my best regards from Jeløen. As you will remember, I was very fortunate to acquire one of your paintings from there some time ago.” (Letter K 3370)

Max Strasberg wrote more specifically a few weeks later. He had the painting reframed in Wrocław, and it had already been shown to the director of the local art museum, who reacted enthusiastically. “I believe the museum here in Wrocław would like to borrow the painting from me for four to six weeks, and I don’t want to refuse the request, because it will give many less affluent people the opportunity to see something beautiful.” (Letter KK 3371)

So Strasberg had succeeded. After five years of persistent requests, he had finally become the owner of a Munch painting: “Spring Day on Jeløya.”

The further fate of Max Strasberg remains hidden in the darkness of history. As a Jew, he was persecuted by the Nazi regime, and apparently tried to leave as few traces as possible during these difficult years. He died in his adopted home of Oslo in 1949 without any direct descendants. “Spring Day on Jeløya” went to his sister, Charlotte, and her husband, Richard Mannheim, who were living in exile in London.

The "Who is Who" of the "Spring Day"

The other famous owners of “Spring Day on Jeløya” read like a “Who's Who” of the 20th century: they include the legendary US financial expert and entrepreneur Josephine Bay (1900–1961) (her husband Charles Ulrich Bay was ambassador to Oslo from 1946 to 1953). Alfons Beaumont Landa, a lawyer and businessman from Palm Beach, was also a social figure of his time – the New York Times even reported on his six-year-old son's birthday party in 1967. Last but not least, of course, is Pål G. Gundersen, who built up an impressive collection of Norwegian art over many decades and is considered a keen expert on Munch. Now “Spring Day on Jeløya” from this remarkable collection is up for auction, allowing a new collector to continue the line of distinguished owners. [AT]