Video

Image du cadre

Autre image

Autre image

Autre image

Autre image

Autre image

Autre image

Autre image

Autre image

Autre image

7

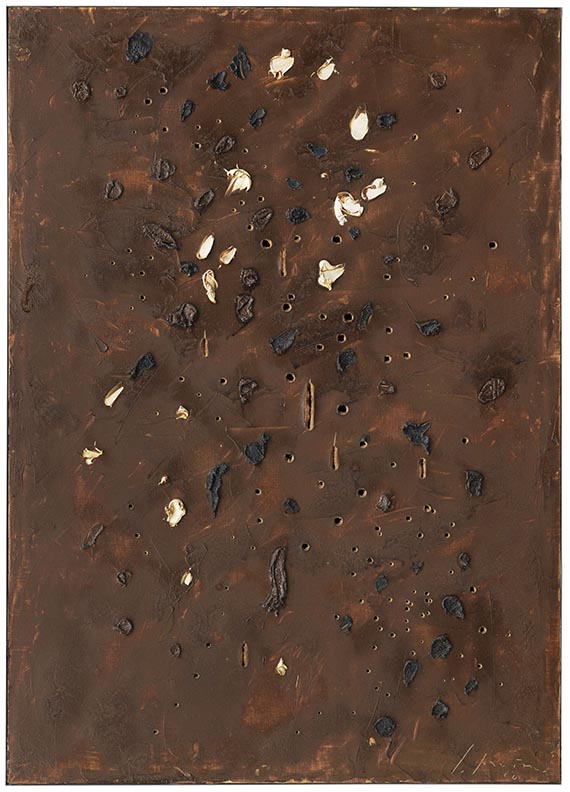

Lucio Fontana

Concetto Spaziale, 1960.

Oil on canvas

Estimation:

€ 800,000 / $ 928,000 Résultat:

€ 838,500 / $ 972,659 ( frais d'adjudication compris)

7

Lucio Fontana

Concetto Spaziale, 1960.

Oil on canvas

Estimation:

€ 800,000 / $ 928,000 Résultat:

€ 838,500 / $ 972,659 ( frais d'adjudication compris)

Lucio Fontana

1899 - 1968

Concetto Spaziale. 1960.

Oil on canvas.

Signed and dated in the lower right. Signed, dated, and titled on the reverse. 85 x 61 cm (33.4 x 24 in). [JS].

• Fontana's canvas piercings, “Buchi,” are widely recognized as one of the most significant positions in post-war art.

• Early, seminal work: from the famous group of works “Buchi,” Fontana’s earliest “Concetti Spaziali.”

• Unique: scarce combination of “Buchi,” “Tagli,” and impasto elements.

• Captivating aesthetics: remarkable cosmic depth and plasticity thanks to the impasto black and white touches.

• International exhibition history and part of a German private collection of international post-war art since 1982.

• Museum quality: works from this creative period are in international collections like the Museum of Modern Art and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York.

PROVENANCE: Galleria Lombardi, Milan.

Art Mari Runnqvist, Stockholm.

Private collection, Hesse (acquired from the above in 1982).

EXHIBITION: Lucio Fontana. Peintures 1960-1964, Galerie Bonnier, Lausanne, Sept./Oct. 1965 (with the label on the stretcher).

Breslavia-Warsaw: Breslavia, Muzeum Narodowe, Dec. 1976 - Jan. 1977; Warsaw, Centralne Biuro Wystaw Artystycznych, Jan./Feb. 1977; Malastrwo Wloskie 1950-1970, exhibition organized by the Quadriennale Nazionale Arte di Roma (with illu.).

Pittura Italiana 1950-1970, Sala Scipka 6, Sofia, May 12-June 6, 1977; Villa Malpensata, Lugano, June-Aug. 1977, exhibition organized by the Quadriennale Nazionale Arte di Roma (with illu.).

Utopia: Arte italiana 1950-1993. An exhibition of the Salzburg Festival in collaboration with The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York, and Galerie Taddeus Ropac, Salzburg, July 24–August 31, 1993; Paris, September 15–October 10, 1993, p. 71 and p. 134 (with illu.).

On permanent loan to the Kunstmuseum Luzern (1988–1994).

On permanent loan to the Kunsthalle Mannheim (1994–2007).

On permanent loan to the Galerie der Stadt Stuttgart (2007–2023).

Lucio Fontana. Erwartung, Von der Heydt-Museum, Wuppertal, October 8, 2024–January 12, 2025, p. 80, cat. no. 39 (with illu.).

LITERATURE: Enrico Crispolti, Lucio Fontana, Catalogue raisonné of sculptures, paintings, and environments, Milan 2015, vol. I, p. 416, CR no. 60 O 15 (with ill.).

-

Enrico Crispolti (ed.), Lucio Fontana, Vol. II: Catalogue raisonné des peintures, sculptures et environnementes spatiaux, compiled by Enrico Crispolti, Brussels 1974, pp. 72/73 (with ill.).

Enrico Crispolti, Fontana. Catalogo generale, Milan 1986, vol. I, p. 251 (with ill.).

“ The hole is my discovery, period; and after this discovery, I may as well rest in peace [..].”

Lucio Fontana, 1960s, quoted in: Barbara Hess, Lucio Fontana 1899–1968, Cologne 2006, p. 7.

“Say what you want about the holes; but a new and purified artistic movement will emerge from them [..]."

Lucio Fontana, 1953, quoted in: Barbara Hess, Lucio Fontana 1899-1968, Cologne 2006, p. 8.

1899 - 1968

Concetto Spaziale. 1960.

Oil on canvas.

Signed and dated in the lower right. Signed, dated, and titled on the reverse. 85 x 61 cm (33.4 x 24 in). [JS].

• Fontana's canvas piercings, “Buchi,” are widely recognized as one of the most significant positions in post-war art.

• Early, seminal work: from the famous group of works “Buchi,” Fontana’s earliest “Concetti Spaziali.”

• Unique: scarce combination of “Buchi,” “Tagli,” and impasto elements.

• Captivating aesthetics: remarkable cosmic depth and plasticity thanks to the impasto black and white touches.

• International exhibition history and part of a German private collection of international post-war art since 1982.

• Museum quality: works from this creative period are in international collections like the Museum of Modern Art and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York.

PROVENANCE: Galleria Lombardi, Milan.

Art Mari Runnqvist, Stockholm.

Private collection, Hesse (acquired from the above in 1982).

EXHIBITION: Lucio Fontana. Peintures 1960-1964, Galerie Bonnier, Lausanne, Sept./Oct. 1965 (with the label on the stretcher).

Breslavia-Warsaw: Breslavia, Muzeum Narodowe, Dec. 1976 - Jan. 1977; Warsaw, Centralne Biuro Wystaw Artystycznych, Jan./Feb. 1977; Malastrwo Wloskie 1950-1970, exhibition organized by the Quadriennale Nazionale Arte di Roma (with illu.).

Pittura Italiana 1950-1970, Sala Scipka 6, Sofia, May 12-June 6, 1977; Villa Malpensata, Lugano, June-Aug. 1977, exhibition organized by the Quadriennale Nazionale Arte di Roma (with illu.).

Utopia: Arte italiana 1950-1993. An exhibition of the Salzburg Festival in collaboration with The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York, and Galerie Taddeus Ropac, Salzburg, July 24–August 31, 1993; Paris, September 15–October 10, 1993, p. 71 and p. 134 (with illu.).

On permanent loan to the Kunstmuseum Luzern (1988–1994).

On permanent loan to the Kunsthalle Mannheim (1994–2007).

On permanent loan to the Galerie der Stadt Stuttgart (2007–2023).

Lucio Fontana. Erwartung, Von der Heydt-Museum, Wuppertal, October 8, 2024–January 12, 2025, p. 80, cat. no. 39 (with illu.).

LITERATURE: Enrico Crispolti, Lucio Fontana, Catalogue raisonné of sculptures, paintings, and environments, Milan 2015, vol. I, p. 416, CR no. 60 O 15 (with ill.).

-

Enrico Crispolti (ed.), Lucio Fontana, Vol. II: Catalogue raisonné des peintures, sculptures et environnementes spatiaux, compiled by Enrico Crispolti, Brussels 1974, pp. 72/73 (with ill.).

Enrico Crispolti, Fontana. Catalogo generale, Milan 1986, vol. I, p. 251 (with ill.).

“ The hole is my discovery, period; and after this discovery, I may as well rest in peace [..].”

Lucio Fontana, 1960s, quoted in: Barbara Hess, Lucio Fontana 1899–1968, Cologne 2006, p. 7.

“Say what you want about the holes; but a new and purified artistic movement will emerge from them [..]."

Lucio Fontana, 1953, quoted in: Barbara Hess, Lucio Fontana 1899-1968, Cologne 2006, p. 8.

“Buchi” – pivotal point and origin of the “Concetti spaziali”

„Slashing His Way to the Sublime- Lucio Fontana made abstraction dangerous by breaking through the surface of a painting. His innovations astound at New York museums.“ wrote the New York Times on the occasion of the major, long-overdue Fontana retrospective “Lucio Fontana. On the Threshold” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2019.

Even today, the radical artistic gesture that the celebrated Italian artist used to revolutionize painting in the mid-20th century still seems extraordinarily strange from the perspective of our traditional viewing habits. The New York Times, for example, described Fontana’s works as if they were from another planet. With his legendary “Buchi” (holes) from the late 1940s, Fontana broke free from the confines of traditional panel painting and, as a result of this destructive act, paradoxically became the creator of a sensual, ethereal aura, as exemplified by the present “Concetto spaziale” in a rich copper tone. In addition to his striking “Buchi,” Fontana accentuated and deepened the opaque painted canvas with additional small “Tagli” (cuts) and the sparing use of impasto dots in black and white.

It is not only in retrospect that art historians have come to appreciate his first perforated papers and canvases, which he started creating in 1949, as the pivotal moment in his entire artistic career; the artist himself also regarded them as such. Among art historians, Fontana's radical gesture of his first perforations, the “Buchi,” as Fontana called this central work group, is celebrated as a crucial point of reference for post-war art in Europe. The name of an artist is rarely so closely associated with a single gesture, a single artistic achievement, as it is in the case of Fontana, who focused his work on piercing the canvas and, about ten years later, on cutting it. When Fontana first punctured a piece of paper mounted on canvas from the back with numerous holes in 1949, instead of drawing on it, so that the displaced material bulged out at the edges, thus extending the two-dimensional pictorial space into the third dimension, he probably did not yet realize that this moment would be the late and decisive turning point in his artistic career. Fontana was already 50 years old at the time and could look back on a career he had primarily devoted to sculpting.

Pioneer and companion - Fontana's “Concetti Spaziali”: radical and progressive

To this day, Fontana is still identified foremost for his famous “Concetti spaziali” (Spatial Soncepts), a generic title under which the artist grouped both his “Buchi” (Holes) and the “Tagli” (Cuts) that followed about a decade later. At the time, however, the radical step of piercing the support was met with great disbelief. Fontana noted: "Laughter for many years! [..] People said to me: ‘What are you doing? You of all people, Lucio, you are such an excellent sculptor ...’ For them, I was good before and an idiot after. And I managed to participate in the Biennale [of Venice in 1950] and fool the commission, because they had already invited me to show my sculptures! However, I didn't say anything and went to the Biennale with 20 perforated canvases. You can imagine the reaction: ‘These aren't sculptures, they're paintings!’ [..] For me, they are perforated canvases that represent a sculpture, a new fact in sculpture." (quoted from: Barbara Hess, Lucio Fontana, Cologne 2006, p. 8). Today, Fontana is considered one of the most important pioneers of the European post-war avant-garde.

Fontana's radical pictorial concept, shattering the boundaries of the canvas and our traditional viewing habits, was a decisive catalyst for a young European avant-garde that would subsequently initiate a radical redefinition of art. In 1962, Henk Peeters summoned all the avant-garde artists in search of a radical new beginning in art to his legendary exhibition “Nul 1962” at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam: In addition to Fontana's “Concetti Spaziali,” the exhibition also featured works by internationally acclaimed artists such as Piero Manzoni, Enrico Castellani, Jan Schoonhoven, Günther Uecker, and Otto Piene. However, Fontana, who was from an earlier generation, is considered the pioneering driving force behind these critical positions, as his Spazialismo movement dates back to 1947. Above all, Manzoni's “Achromés" from around 1960 is also regarded as an epochal creation of this artistic revolution. The significantly reduced color palette, the renunciation of form and creative style, and the dissolution of traditional canvas boundaries generate a completely new, minimalist aesthetic that, as a kind of negation of painting, abruptly transcends all previous styles.

Art and Space – Fontana's “Concetti Spaziali” and the dissolution of boundaries

Fontana's remarks from the 1960s seem like a description of this subtly arranged composition: “When I work on one of my perforated paintings as a painter, I do not intend to make a painting: I want to open up a space, create a new dimension of art, enter into a relationship with the cosmos, which extends beyond the confined surface of the painting into infinity” (ibid., p. 8). The canvas is no longer solely the vehicle of artistic imagination, but, through its materiality, becomes the center of creative attention, opening up into the third dimension and allowing us to see deep into the void of infinity through holes and cuts.

The dissolution of a painting's boundaries into the cosmic, as Fontana mentioned, is intensified in this painting by its deep, copper-brown palette and starry, luminous accents, which lend this poetic composition an extraordinary depth and breathtaking radiance.

It is no coincidence that the first satellite images of Earth were shown on television in the year this painting was created, and that the decades of great enthusiasm for space and the moon came to an end with the moon landing in 1969, with scientific research into its crater surface at the focus of international space travel. Fontana had already expressed the following in his 1948 “Secondo manifesto dello Spazialismo” (Second Manifesto of Spatialism): “[…] today, we, the artists of Spazialismo, have fled our cities, broken through our shell, our physical crust, and looked down on ourselves from above, photographing the Earth from flying rockets.” (quoted from: Enrico Crispolti, Lucio Fontana, vol. I, p. 115, Milan 2006).

Fontana had already engaged with the contemporary achievements of space photography and scientific knowledge of the universe at the beginning of his revolutionary Spazialismo movement in the late 1940s, when technical innovations were gradually enabling astrophotography to deliver more precise images from space. For Fontana, however, the unknown, increasingly explored through science and technology, is always also a place of creativity and imagination. In his “Manifesto tecnico” of 1951, he wrote: “The work of art cannot last forever, but the imagination of human creativity exists, and when man ends, infinity continues.” (quoted from: Crispolti 1986: vol. 1, 36f.). In addition, Fontana's very first Concetto Spaziale was a black-painted plaster sculpture made in 1947, which he initially designated Scultura Spaziale. The sculpture is composed of spherical, roughly shaped elements, a structure reminiscent of geological formations or primitive lava rock, which encapsulates and visualizes space. It was in this manner that Fontana first discovered a pictorial formula for the physical boundlessness of space in 1947, a concept that he would continue to explore throughout his career.

With his progressive oeuvre, Fontana, alongside the American Frank Stella, made one of the most significant contributions to the global contemporary quest for spatial liberation in painting. Today, his works are in numerous international collections, including the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York; the Tate Collection, London; the Centre Pompidou, Paris; and the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo. In 2019, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, honored this pioneering oeuvre with the retrospective “Lucio Fontana. On the Threshold.” [JS]

„Slashing His Way to the Sublime- Lucio Fontana made abstraction dangerous by breaking through the surface of a painting. His innovations astound at New York museums.“ wrote the New York Times on the occasion of the major, long-overdue Fontana retrospective “Lucio Fontana. On the Threshold” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2019.

Even today, the radical artistic gesture that the celebrated Italian artist used to revolutionize painting in the mid-20th century still seems extraordinarily strange from the perspective of our traditional viewing habits. The New York Times, for example, described Fontana’s works as if they were from another planet. With his legendary “Buchi” (holes) from the late 1940s, Fontana broke free from the confines of traditional panel painting and, as a result of this destructive act, paradoxically became the creator of a sensual, ethereal aura, as exemplified by the present “Concetto spaziale” in a rich copper tone. In addition to his striking “Buchi,” Fontana accentuated and deepened the opaque painted canvas with additional small “Tagli” (cuts) and the sparing use of impasto dots in black and white.

It is not only in retrospect that art historians have come to appreciate his first perforated papers and canvases, which he started creating in 1949, as the pivotal moment in his entire artistic career; the artist himself also regarded them as such. Among art historians, Fontana's radical gesture of his first perforations, the “Buchi,” as Fontana called this central work group, is celebrated as a crucial point of reference for post-war art in Europe. The name of an artist is rarely so closely associated with a single gesture, a single artistic achievement, as it is in the case of Fontana, who focused his work on piercing the canvas and, about ten years later, on cutting it. When Fontana first punctured a piece of paper mounted on canvas from the back with numerous holes in 1949, instead of drawing on it, so that the displaced material bulged out at the edges, thus extending the two-dimensional pictorial space into the third dimension, he probably did not yet realize that this moment would be the late and decisive turning point in his artistic career. Fontana was already 50 years old at the time and could look back on a career he had primarily devoted to sculpting.

Pioneer and companion - Fontana's “Concetti Spaziali”: radical and progressive

To this day, Fontana is still identified foremost for his famous “Concetti spaziali” (Spatial Soncepts), a generic title under which the artist grouped both his “Buchi” (Holes) and the “Tagli” (Cuts) that followed about a decade later. At the time, however, the radical step of piercing the support was met with great disbelief. Fontana noted: "Laughter for many years! [..] People said to me: ‘What are you doing? You of all people, Lucio, you are such an excellent sculptor ...’ For them, I was good before and an idiot after. And I managed to participate in the Biennale [of Venice in 1950] and fool the commission, because they had already invited me to show my sculptures! However, I didn't say anything and went to the Biennale with 20 perforated canvases. You can imagine the reaction: ‘These aren't sculptures, they're paintings!’ [..] For me, they are perforated canvases that represent a sculpture, a new fact in sculpture." (quoted from: Barbara Hess, Lucio Fontana, Cologne 2006, p. 8). Today, Fontana is considered one of the most important pioneers of the European post-war avant-garde.

Fontana's radical pictorial concept, shattering the boundaries of the canvas and our traditional viewing habits, was a decisive catalyst for a young European avant-garde that would subsequently initiate a radical redefinition of art. In 1962, Henk Peeters summoned all the avant-garde artists in search of a radical new beginning in art to his legendary exhibition “Nul 1962” at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam: In addition to Fontana's “Concetti Spaziali,” the exhibition also featured works by internationally acclaimed artists such as Piero Manzoni, Enrico Castellani, Jan Schoonhoven, Günther Uecker, and Otto Piene. However, Fontana, who was from an earlier generation, is considered the pioneering driving force behind these critical positions, as his Spazialismo movement dates back to 1947. Above all, Manzoni's “Achromés" from around 1960 is also regarded as an epochal creation of this artistic revolution. The significantly reduced color palette, the renunciation of form and creative style, and the dissolution of traditional canvas boundaries generate a completely new, minimalist aesthetic that, as a kind of negation of painting, abruptly transcends all previous styles.

Art and Space – Fontana's “Concetti Spaziali” and the dissolution of boundaries

Fontana's remarks from the 1960s seem like a description of this subtly arranged composition: “When I work on one of my perforated paintings as a painter, I do not intend to make a painting: I want to open up a space, create a new dimension of art, enter into a relationship with the cosmos, which extends beyond the confined surface of the painting into infinity” (ibid., p. 8). The canvas is no longer solely the vehicle of artistic imagination, but, through its materiality, becomes the center of creative attention, opening up into the third dimension and allowing us to see deep into the void of infinity through holes and cuts.

The dissolution of a painting's boundaries into the cosmic, as Fontana mentioned, is intensified in this painting by its deep, copper-brown palette and starry, luminous accents, which lend this poetic composition an extraordinary depth and breathtaking radiance.

It is no coincidence that the first satellite images of Earth were shown on television in the year this painting was created, and that the decades of great enthusiasm for space and the moon came to an end with the moon landing in 1969, with scientific research into its crater surface at the focus of international space travel. Fontana had already expressed the following in his 1948 “Secondo manifesto dello Spazialismo” (Second Manifesto of Spatialism): “[…] today, we, the artists of Spazialismo, have fled our cities, broken through our shell, our physical crust, and looked down on ourselves from above, photographing the Earth from flying rockets.” (quoted from: Enrico Crispolti, Lucio Fontana, vol. I, p. 115, Milan 2006).

Fontana had already engaged with the contemporary achievements of space photography and scientific knowledge of the universe at the beginning of his revolutionary Spazialismo movement in the late 1940s, when technical innovations were gradually enabling astrophotography to deliver more precise images from space. For Fontana, however, the unknown, increasingly explored through science and technology, is always also a place of creativity and imagination. In his “Manifesto tecnico” of 1951, he wrote: “The work of art cannot last forever, but the imagination of human creativity exists, and when man ends, infinity continues.” (quoted from: Crispolti 1986: vol. 1, 36f.). In addition, Fontana's very first Concetto Spaziale was a black-painted plaster sculpture made in 1947, which he initially designated Scultura Spaziale. The sculpture is composed of spherical, roughly shaped elements, a structure reminiscent of geological formations or primitive lava rock, which encapsulates and visualizes space. It was in this manner that Fontana first discovered a pictorial formula for the physical boundlessness of space in 1947, a concept that he would continue to explore throughout his career.

With his progressive oeuvre, Fontana, alongside the American Frank Stella, made one of the most significant contributions to the global contemporary quest for spatial liberation in painting. Today, his works are in numerous international collections, including the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York; the Tate Collection, London; the Centre Pompidou, Paris; and the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo. In 2019, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, honored this pioneering oeuvre with the retrospective “Lucio Fontana. On the Threshold.” [JS]